After a run of 22 years, Justart, our project working with young people referred by the Bradford Youth Justice Service, is coming to an end. We asked Vic, who has worked on the project (variously as manager, tutor and mentor) for its whole history, to tell us more.

Justart was originally set up when Hive (then known as Kirkgate Studios and Workshops), in partnership with the Youth Justice Service (then known as the Bradford Youth Offending Team – YOT), made a successful bid to the Neighbourhood Support Fund. I was employed and, with the guidance and support of the YOT Education Team under Rob Mooney, set up a program of workshop sessions.

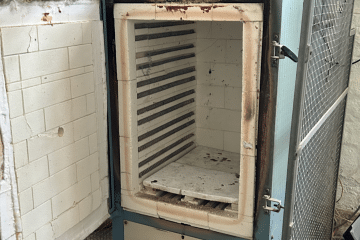

Initially, our funding was sufficient to enable us to provide five sessions per week, engaging up to 15 young people per week in a range of art and craft activities: ceramics, woodwork, sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, photography and IT. Christine Godfrey was engaged as a ceramics tutor, then Graham Dawson was added to our team as an IT tutor.

A route to rehabilitation

The broad aims of Justart were to engage young people through a positive, creative approach, to help build skills, raise self-esteem, encourage personal development, to provide a route to rehabilitation, to help to reintegrate young people into the community, to act as a gateway to further opportunities.

Individuals have also been encouraged to participate in various outreach projects, helping to produce and install artwork in community settings. Examples of these include two large ceramic murals; one installed in Victoria Hall in Saltaire, another in Westbourne Green Medical Centre in Manningham.

George the Duck

Our young people also contributed artworks for local festivals in Bradford, Saltaire and Shipley. Memorable examples of these include a ‘life-sized’ Troll made from chicken wire stuffed with soft toys, installed as if climbing from under the canal bridge at Saltaire, and ‘George the Duck’, a metre-high version of a fairground hook-a-duck, which ended up being towed along the same canal by a barge.

George the Duck featured too, in the annual ‘Showcase’ event, organized by YOT and held at the Bradford Alhambra (and for which we also designed the projected logo-backdrop). This event predominantly featured theatrical performances by various YOT-associated youth groups, and showcased young people’s achievements in front of a large audience of professionals, project representatives, participants’ families and friends. Justart helped some of these groups by making stage props: for one group we made a three-quarter scale canoe. After one of these events, ‘George the Duck’ was ‘adopted by the then-manager of Bradford YOT, Paul O’Hara, and accompanied him as a prop when he was a speaker at various conventions.

Our participants were also able to exhibit their personal artworks annually, at the Shipley Library Gallery Space and at another YOT Awards event held at Valley Parade football ground.

Tracey Emin and McDonalds

Occasionally, our groups of young people were taken to visit art galleries. These were most commonly the local ones – Cartwright Hall and the 1853 Gallery in Salts Mill.

Memorably though, Graham and myself once took four young people on a train trip to the Liverpool Tate. This is mainly memorable for the positive atmosphere generated by the group – their high spirits, excitement and happy state (manifesting itself at one point, through an impromptu dance routine on the station platform). These were enthusiastic travellers, and the group had a cohesion that made it seem like a family outing.

They were unimpressed, sadly, by the Tracy Emins, the Gillian Wearings, and even the Turner watercolours they saw at the Tate, and much more impressed and appreciative of the McDonalds burgers we consumed before the return trip.

Changing funding

After about ten years of being funded, with consecutively smaller amounts, by various charitable organisations, Justart continued in a smaller way, with just myself as tutor and with two or three sessions each week.

The tendency then was for working with smaller groups and, generally, more ‘difficult’ cases. Bradford YOT recognised our ability to engage ‘hard-to-reach’ individuals, those who it had proved difficult to engage elsewhere. The YJS now funded us from their own budget, and latterly, when Bradford council took responsibility for their finances, our project was effectively Council funded and we had to tender for the YJS work.

We were successful in our last bid for funding and were awarded a two-year contract, just prior to the onset of COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdowns. During that time we produced a range of art and craft ‘packs’, enabling young people to work on projects from their homes. Those two years are now up, and the decision has been made by the YJS not to renew the provision.

Mirages and outcomes

To help me write this little history, I dug out some old promotional material: leaflets explaining our provision and reports evidencing numbers, attendance records, levels of attainment and outcomes. These comprise mainly statistics, categories and ‘specialist’ terms, in language recognisable and acceptable to professionals and funders. They can come across as dry, ‘bullet-pointedly’ efficient and official.

Outcomes have always been difficult to pin down. For me, an outcome is a bit like a mirage, in that it refers to an ‘end point’ that doesn’t exist. Our former participants’ lives continue outside and beyond Justart. Confidentiality and safeguarding issues rightly dictate that we can’t follow their lives, and can’t expect feedback on how their lives develop. There’s an adage used, that if we don’t see or hear about former participants, that is a positive sign, as it suggests that they’ve been able to stay out of trouble and have settled into a more stable existence.

Over the years then, I’d estimate that Justart has worked with a thousand plus young people. But of course that number is not just a statistic. That number reflects the lives of a thousand plus individuals and their thousand plus stories, whose plot or development we can only wonder about. I’m quite confident though, that in the overwhelming majority of those stories, if not all of them, Hive and Justart have featured as positive episodes or chapters.

‘Arthur’

I do wonder how some of our former participants are faring now. Occasionally they return to visit Hive. The most recent example was ‘Arthur’ (not his real name). Arthur had attended for quite a protracted period, spread over a couple of our formative years. He was positive, gregarious, engaging, had a dry humour and got on well with tutors and other Hive users as well as with his peers.

He particularly liked working and chatting in the pottery. He showed interest in what the older users were making and described the atmosphere at Hive as “laid back but buzzing”. He would often come out with comments reflecting a kind of convoluted but admirable logic, bordering on the wisdom one might expect to encounter when reading someone like Albert Camus: on being encouraged to learn something in an IT session he politely declined, justifying his stance by saying, “If I learn too much, people will expect me to go on to look for a job or to go to college”. Or, in Camus’ words, reflecting the way of being of someone for whom ‘what he demands of himself is to live solely with what he knows, to accommodate himself to what is, and to bring in nothing that is not certain’ (1). In fact he learned a lot, not least in developing his appreciation of arts and crafts, and his practical and social skills.

Arthur was a habitual ‘offender’. He kept getting arrested for relatively minor crimes, so there’d be a gap in his attendance, but then he’d return the same as ever. We stopped seeing him when at last he successfully completed a community order and, reaching 18, became an adult – beyond the remit of YOT and ourselves. Eighteen or so years later, now in his mid-thirties, Arthur visited Justart- an impulsive social visit. He stopped and chatted with our group and enthused about his time on the project. He filled us in on his current situation: he was settled, had a job, a partner, a child, a home. He was keeping out of trouble. He was happy.

‘Chris’

Other former participants come to mind. Some of their stories are not so ‘pretty’. I wonder how ‘Chris’ is getting on. He had attended Justart for a year or so. He was ‘a dream’ to work with – communicative, cheerful and willing. He tried everything and produced some impressive work. But then he committed an offence and was locked up.

I last saw him, aged 19 or 20, when I bumped into him in Bradford city centre. He was still expressively cheerful, but he was sporting a long scar on his neck. He’d been released from prison, with the scar as a souvenir resulting from an unpaid tobacco debt. But he had a place to live and a new girlfriend and was looking for a job.

‘Liam’

I wonder how ‘Liam’ is getting on. He’d been referred to us by YOT having been excluded, first from school, and then from his Pupil Referral Unit after some violent behaviour toward staff. In common with a large percentage of our referrals, Liam had some learning difficulties. He had been diagnosed as having ADHD, and had quite significant sensory problems: bright lights caused him distress, and he reacted badly to the feel of certain materials.

At Justart, we worked hard at addressing his needs: adapting our provision to enable him to engage; persevering and encouraging him to persevere; finding solutions to make his activities comfortable and productive. Eventually he settled down, found ways of working effectively and produced a portfolio of work. A report on his progress was sent to the PRU he had been excluded from. They visited him at Justart, chatted with him, looked at the work he’d done work, then agreed to give him another chance at the PRU.

‘Jamie’

‘Jamie’ is another former participant I wonder about now and then. He’d attended Justart, again for a long period, was calm, communicative and willing to try his hand at everything we offered. He completed his community-based court order successfully and stayed away from committing crime.

Jamie lived in care. He could be described as not being as streetwise as most of our young people, perhaps as naïve or relatively ‘innocent’. On reaching 18, and thus leaving care, he was appointed a flat where he would be expected to live independently. He didn’t know the area, but soon made some acquaintances. Unfortunately though, he was taken advantage of by other youths who began (he told us) to use his flat to store stolen goods in. When some of these goods went missing, Jamie was blamed and threatened with violence. Although Jamie had left our project some months earlier, he returned to us for help. We contacted his social worker and helped him retrieve his belongings. The last I heard, he had been reallocated another home in another area. I wonder how he’s getting on, whether he is getting the support he needs.

Intergenerational welcome

One aspect of Justart that has been important has been the intergenerational contact at Hive. Justart has shared the Hive building, its spaces and facilities, with other, predominantly older groups and individual users. From the start 22 years ago, and through the years, it has been to the credit of users (and staff) that there has been a huge sense of welcoming: of tolerance, acceptance and inclusivity.

Young people touring the building have shown interest in other makers’ works and processes and have received encouragement to try things themselves. On creating artwork, they are pleased to be able to show their work to the adults in the building, and invariably have received positive, confidence-boosting responses.

The intergenerational (and intercultural) experience has been positive and mutually beneficial. The warm, welcoming, supportive, stimulating and purposeful nature of the environment and atmosphere at Hive has helped enormously in the successes and longevity of the project.

The best job I’ve had

On a personal level, this has been the best job I’ve had: the most rewarding. I feel I’ve had the opportunity to work at something that is worthwhile: of value both in terms of helping young people who have experienced a tough time, and in the project’s contribution to the community. It has been stimulating, challenging, motivating and meaningful. It has helped my personal development too: I’ve had to become more vigilant, aware, spontaneous, responsive, empathic, effective – more ‘woke’ if you like, in the best, original sense of the term.

While I’ve worked with a diverse range of community groups, I’ve particularly enjoyed working with this group, with individuals who might typically be characterized as being cheeky, subversive and rebellious (qualities I admire!). They are reliably unpredictable, and I’ve had to hone my improvisational skills to work effectively with them. They are generally the most honest group (ironically) that I’ve worked with, in the sense that they have mostly expressed exactly what they think about things and how they feel. I’ve been gratified when they’ve felt able to be frank and open in communicating their experiences, opinions, worries and hopes.

I’ve seen transformations revealing other sides to individuals. Characters who might initially be reserved or hesitant, or suspicious, resistant or even scowling, have changed to reveal ‘alter egos’ engaged in creative activities: relaxed, chatty, immersed in making, in ‘playing’ with materials. ‘Hardened’ teenagers, who in making art appear to have managed to retrieve, at least temporarily, a kind of innocence that had been hidden away too early.

Bradford on Duty

Recently, the BBC has been airing a series of documentaries about Bradford: Bradford on Duty (2). One episode, The Next Generation, focused on Bradford’s youth culture and highlighted many problems. Disturbing facts were revealed about high youth offending rates in Bradford – the city with the youngest population of any in the UK – and about the failures of Bradford’s Children’s Services, largely due to rising demand, an insufficient workforce and reduced budgets. Our Council’s budget, we were told, had been reduced by £300 million compared with that of ten years ago, and in that period, Youth Service spending has been cut by 73%. So while they recognize the needs, and appear to know what needs doing to address them, they lack the necessary resources.

All our Futures

At the time when Justart began, Tony Blair’s government had commissioned a report focusing on creativity, culture and education, with the aim of examining and making proposals for enhancing the lives, wellbeing and prosperity of young people (and thus the nation in general). The report, All Our Futures (3), recognized the importance of creativity and contained many contributions and endorsements from professionals working in related fields. Pauline Tambling, then the director of Education and Training for the Arts Council of England wrote:

To me the essence of creative and cultural education is that individuals, in this case young people, find their creative / cultural ‘voice’, develop skills to service this, engage with the creativity and work of others with a view to participating in society. It has to be an active engagement. When it is, it is an answer to other problems: social exclusion, disaffection, etc. But the creative act – whether it is an arts activity or other creative endeavour – has to empower the individual child. At best it critiques and challenges past and current practice and leads to renewal of the individual and society.

Pauline Tambling, All Our Futures

Many positive proposals and recommendations were made in the report and some of these began to be put into effect. But, as outlined above, for over a decade now the funding for youth provision and for creative organizations generally has been drastically reduced. Successive Education Secretaries have sidelined the arts in their reforms of the school curriculum, with schools being encouraged to run on the lines of business models, and with the arts relegated to an optional and outsourced add-on. Similarly, the values of, and opportunities to access, the arts and creativity in higher education are being minimized. To give a current example illustrating a wider trend, in a Guardian article from 27th of June (4), in which various contributors are critical of Sheffield Hallam University’s decision to drop its English Literature degree course, the author Sarah Perry, says:

I suspect this is only the latest symptom in the disease creeping across education at all levels, in which learning has been stripped of everything but the most utilitarian aims, designed to form minds into nothing but cogs in the capitalist machine. It’s dismal and dehumanizing, and I’m afraid its effects will be far-reaching.

Sarah Perry

Terry Eagleton manages his despair and frustration in writing on this theme by injecting some humour:

In moving some of its academic staff to new premises, one British University recently issued an edict severely restricting their ability to keep books in their miniscule offices. The idea of having a personal collection of books is becoming as archaic as Bill Haley or drainpipe trousers. The dream of our universities’ boneheaded administration is of a bookless and paperless environment, books and paper being messy, crumply stuff incompatible with a gleaming neo-capitalist wasteland consisting of nothing but machines, bureaucrats and security guards. Since students are also messy, crumply stuff, the ideal would be a campus on which no such inconvenient creatures were in sight. The death of the humanities is now an event waiting on the horizon (5).

Terry Eagleton

The findings and recommendations of All Our Futures, in which it was recognized that,

Art is not a diversion or a side issue. It is the most educational of human activities and a place in which the nature of morality can be seen,

Iris Murdoch

seem to have been dismissed by the current administration. As Susan Hinchcliffe, the leader of Bradford Council, admits in Bradford On Duty, demand is high but funding is reduced, and there is an increasing reliance on the input of voluntary and charitable organisations.

A Haven of Hope

Hive is one of those organisations. I’ve always though of Hive as a haven, a refuge, a sanctuary from the frenetic busyness and persistent pressures of the outside world; a kind of Oasis where people commune and create, find meaningfulness and a sense of wellbeing. And Hive has survived. It is soon to celebrate its 40th anniversary and I’m sure will continue to do its valuable work in providing creative opportunities for all. There are positive-looking developments; hopeful signs for the future.

Work will soon start with The Kirkgate Centre upstairs on an ambitious building project to improve the working environment for both organisations. And I’m sure there will be further opportunities, perhaps for more outreach work (since the space within Hive is limited), arising from Bradford’s success in securing City of Culture status for 2025.

So while it’s sad that Justart has come to an end, I’ve felt privileged to have been able to do this work for such a long period. And I’d like to thank all those involved in enabling, supporting and participating in it.

Vic Buta

References

- Albert Camus, 4. Absurd Freedom, The Myth of Sisyphus, p53, Vintage books, 2018

- BBC Documentary, 3. The Next Generation, Bradford On Duty series 1, 2022

- Creativity, Culture, Education, All Our Futures, The National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education, 1998

- Sally Weale (Education Correspondent), Philip Pullman Leads Outcry…, The Guardian, 27th June 2022

- Terry Eagleton, Culture, p153, Yale University Press, 2018